By Bob Difley

Just knowing that you can legally boondock almost anywhere on public lands, such as those managed by the forest service (which is tightening up camping rules so check in with the local office or online first) and BLM, as I wrote in last week’s post, does not tell you exactly how to find these “dispersed” campsites (not within the confines of an organized campground).

Just knowing that you can legally boondock almost anywhere on public lands, such as those managed by the forest service (which is tightening up camping rules so check in with the local office or online first) and BLM, as I wrote in last week’s post, does not tell you exactly how to find these “dispersed” campsites (not within the confines of an organized campground).

You won’t find any signs saying “Campsite Here” or numbered posts designating campsites. No hosts in golf carts will lead you to an open site. No, you have to find them for yourself. Since finding dispersed campsites is more difficult than finding campgrounds, it is one of the features that makes boondocking attractive–there won’t be a lot of RVers competing for the same campsite.

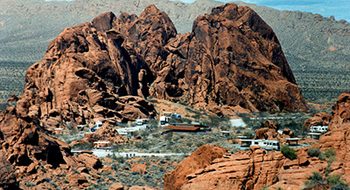

First, become alert so that you notice when you enter public lands. You will recognize national forests or national recreation areas by their familiar brown signs (photo below). Seldom, however, will signs identify BLM lands, which mostly lie in the eleven Western states). Much of the land in the Southwest used by snowbirds in winter is BLM land.

Maps are available from visitor centers in states that contain public lands and on the Public Lands website where shaded areas define lands managed by the BLM, Bureau of Reclamation, National and State Forest Services, Fish and Wildlife Service, Indian Reservations, etc. However, the BLM and some other agencies do not necessarily post signs so you can determine when you enter and leave. Sometimes the only way you can recognize when you are on public land is the absence of “No Trespassing” signs, mailboxes at side road junctions, and locked gates.

Maps are available from visitor centers in states that contain public lands and on the Public Lands website where shaded areas define lands managed by the BLM, Bureau of Reclamation, National and State Forest Services, Fish and Wildlife Service, Indian Reservations, etc. However, the BLM and some other agencies do not necessarily post signs so you can determine when you enter and leave. Sometimes the only way you can recognize when you are on public land is the absence of “No Trespassing” signs, mailboxes at side road junctions, and locked gates.

Lacking these, go for it. Even if you see a gate, but it is not locked, it is OK to enter. The gate is to keep grazing cattle from straying off the land and into the road. Just be sure to close it once you enter. Many of these public land side roads were originally built to support logging and cattle trucks, and are therefore substantial enough to support your rig–as long as they have been maintained.

Train yourself to focus on spotting side roads when crossing public land, even if you are not currently looking for a campsite. Save the location to your GPS or indicate it on a paper map for next time you pass through–when you may need a campsite. Not all roads will yield acceptable campsites, but by spotting certain characteristics, you can make an educated guess whether you will find one.

Pass by roads with these features: narrow or winding road; overhanging tree branches; deep ruts; soft, sandy, or muddy road surface; debris on road; road soon climbs a hill or drops into a canyon; cattle on road; bears picking blueberries. Look for these signs: wide, level road; clear overhead; evidence of use by large vehicles; turn around room; large, level parking (potential campsites); other boondockers.

You may not be able to spot all the positive signs from the main road. If not, walk in a ways (the walk will also stretch out your stiff joints from sitting too long) to see how it looks. If it looks like it has potential, I highly recommend that you unhitch and drive your tow or toad in to locate a spot. Once you find one, return to retrieve your rig and move to the site.

This may seem like a lot of work for a single overnight spot, but with a little experience you will begin to recognize those roads that are likely to have campsites, and walking in a hundred yards or so will often find you an acceptable overnight spot. Then make a record of the spot for the next time through. You may think you will remember it, but your short term memory isn’t what it used to be.

For longer boondocking stays, find a suitable spot for the first night, even at an organized campground, then explore the next day (pick up maps from the local office of the management agency) so you can find a spot far enough off the access road that you can’t hear the traffic, or beside a stream, or in a wildflower covered meadow. For several days of camping, it is worth expending a bit more time and effort to find the perfect campsite. And from then on it will be yours.

For more RVing articles and tips take a look at my Healthy RV Lifestyle website, where you will also find my ebooks: BOONDOCKING: Finding the Perfect Campsite on America’s Public Lands (PDF or Kindle), 111 Ways to Get the Biggest Bang for your RV Lifestyle Buck (PDF or Kindle), and Snowbird Guide to Boondocking in the Southwestern Deserts (PDF or Kindle), and my newest, The RV Lifestyle: Reflections of Life on the Road (Kindle reader version). NOTE: Use the Kindle version to read on iPad and iPhone or any device that has the free Kindle Reader app.